The Anglo-Zulu War (1879)

- Ray Via II

- Sep 12, 2025

- 7 min read

The Anglo-Zulu War of 1879 was fought between the British Empire and the Zulu Kingdom of southern Africa. Its origins lay in the British drive for confederation in South Africa, a plan promoted by Secretary of State for the Colonies Lord Carnarvon. His vision sought to unify the British colonies, the Boer republics, and independent African states into a single political federation under London’s control. To implement this policy, Sir Bartle Frere, the British High Commissioner for Southern Africa, was dispatched to Natal. He viewed the Zulu Kingdom under King Cetshwayo kaMpande as the greatest obstacle to this plan, since the Zulu amabutho regimental system represented both a strong military force and a political model incompatible with British authority.

Tensions had already been heightened by Britain’s annexation of the Transvaal in 1877 under Theophilus Shepstone, which brought the British into direct contact with the Zulu border. The Utrecht district disputes between Boer settlers and Zulu clans gave Frere further grounds for confrontation. In December 1878, he presented Cetshwayo with an ultimatum demanding the disbanding of the Zulu army, the acceptance of missionaries, payment of fines in cattle, the extradition of certain Zulus to Boer courts, and British oversight of Zulu affairs. These demands were designed to be impossible to accept, and when Cetshwayo refused, Frere authorized war without explicit approval from London.

Opening of the War

In January 1879, British forces under Lieutenant General Lord Chelmsford crossed the Tugela and Buffalo rivers into Zululand. Chelmsford had about 17,000 men organized into three invasion columns:

No. 1 Column (Pearson) – 5,000 men including the 3rd (East Kent) Regiment, the 99th (Lanarkshire) Regiment, and the Naval Brigade with two 7-pounder field guns.

No. 2 Column (Durnford) – about 2,500 Natal Native Contingent auxiliaries and colonial irregulars supported by the Natal Mounted Police.

No. 3 Column (Glyn, with Chelmsford) – the main striking force of 7,000 men, including the 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 24th (South Wales Borderers) Regiment, the 2nd Battalion 3rd Regiment (The Buffs), and several batteries of Royal Artillery.

The British soldiers carried Martini-Henry .450 caliber breech-loading rifles, capable of fast, accurate fire at long range. Each infantryman carried 70 rounds in his pouch, with ammunition wagons in support. For close combat, they had bayonets. Cavalry and mounted units carried Swedish steel sabers and Webley revolvers. Supporting them were 7-pounder field guns, rocket batteries, and, in the later campaign, Gatling guns, which proved decisive at Ulundi.

The Zulu army, though not equipped with firearms on the same scale, possessed a formidable organization. King Cetshwayo’s amabutho regiments were drawn from a national system of age-based cohorts, trained for years in discipline and rapid maneuver. Each warrior carried a large cowhide shield (isihlangu) and the iconic short stabbing spear (iklwa) developed by Shaka Zulu, alongside traditional throwing spears (assegai) and knobkerries (clubs). While some Zulus obtained muskets or captured rifles through trade and conflict, they lacked training in marksmanship and ammunition supply, making firearms a minor part of their arsenal. Zulu strategy relied on mobility, encirclement, and shock tactics, often using the famous “horns of the buffalo” formation to envelop the enemy.

The Catastrophe at Isandlwana and the Stand at Rorke’s Drift

On 22 January 1879, Chelmsford split his No. 3 Column and left half the force in camp at Isandlwana. That same day, a Zulu army of about 20,000 warriors under Ntshingwayo kaMahole Khoza and Mavumengwana kaNdlela Ntuli launched a surprise attack. The Zulus overran the camp, killing over 1,300 British and colonial troops, including most of the 1/24th and 2/24th Regiments, despite the defenders’ disciplined volleys. The lack of entrenchments, poor ammunition supply distribution, and underestimation of Zulu numbers turned the battle into Britain’s worst colonial defeat of the century.

That evening, the war’s most famous defense occurred at the nearby mission station of Rorke’s Drift. There, about 150 British soldiers under Lieutenant John Chard of the Royal Engineers and Lieutenant Gonville Bromhead of the 24th Regiment fortified their post with mealie bags and biscuit boxes. They faced more than 3,000 Zulu warriors under Prince Dabulamanzi kaMpande, Cetshwayo’s half-brother. The defenders’ concentrated Martini-Henry fire, combined with bayonet charges, held off the attacks through the night. British losses totaled 17, while Zulu casualties exceeded 300. Eleven Victoria Crosses were awarded, the most for a single action in British history.

The Middle Campaign

After the initial shock, the campaign settled into attritional fighting. On 22 January, Colonel Pearson’s No. 1 Column repelled an ambush at the Battle of Nyezane, before being besieged at Eshowe until April. In the north, Colonel Evelyn Wood commanded a mixed force of regular infantry, irregular mounted units, and artillery. On 28 March, his forces were badly mauled at the Battle of Hlobane, losing over 100 men as mounted irregulars retreated chaotically from the mountain. But the very next day, Wood redeemed his command at the Battle of Kambula, where disciplined infantry squares with artillery and concentrated rifle fire shattered a Zulu impi, killing nearly 2,000 at the cost of about 80 British dead. This was the first major decisive victory for the British in the war.

On 2 April, Chelmsford personally led the relief of Eshowe by defeating a 12,000-strong Zulu force at the Battle of Gingindlovu, using infantry squares and artillery superiority to rout the attackers.

The Advance to Ulundi and the Fall of the Zulu Kingdom

By May and June, reinforcements from Britain increased Chelmsford’s strength to over 30,000 men, including fresh battalions, cavalry units, and artillery batteries equipped with Gatling guns. In July, he prepared for the final offensive against the Zulu capital.

On 4 July 1879, at the Battle of Ulundi, Chelmsford advanced with a massive infantry square supported by cavalry and artillery. Facing him, King Cetshwayo had assembled around 20,000 warriors in a last bid to defend his kingdom. The Zulus charged bravely but were met with devastating volleys from Martini-Henry rifles, Gatling gun streams of fire, and shellfire from field guns. Within hours, the Zulu army was broken, leaving more than 1,500 dead on the field. British losses were about 100. Ulundi was burned, and the war effectively came to an end.

Aftermath

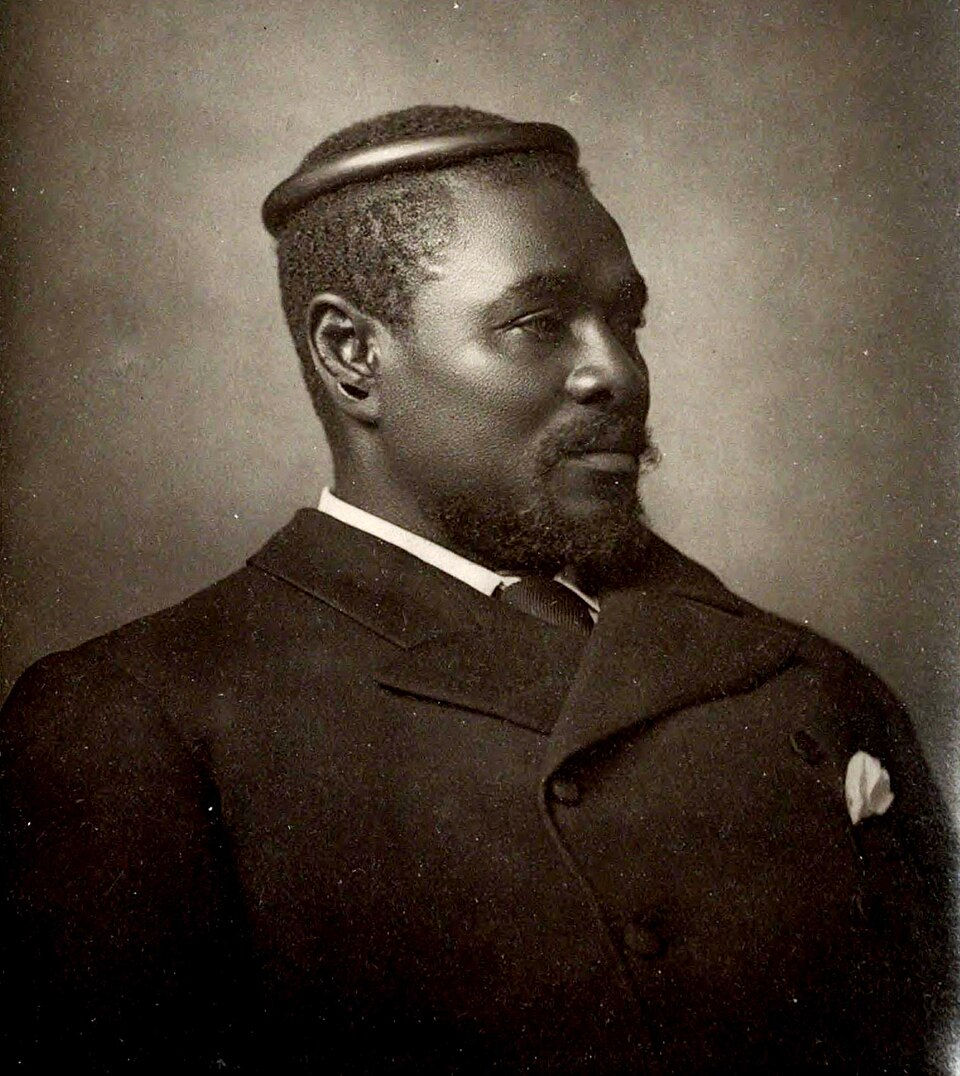

King Cetshwayo was captured in August 1879 and taken into exile first in Cape Town and later in London, where he became a figure of fascination to the British public. The British then divided Zululand into 13 separate chieftaincies, deliberately undermining centralized authority. This fragmentation led to instability and civil conflict. In 1883, Cetshwayo was restored with limited authority, but his enemies, supported by Boer mercenaries, defeated him in 1884. He died later that year under suspicious circumstances, possibly poisoned. By 1887, Britain formally annexed Zululand, extinguishing its independence.

The Anglo-Zulu War revealed the clash between modern industrial firepower and traditional African military organization. At Isandlwana, disciplined Zulu courage and tactical skill brought down a British column. Still, at Kambula, Gingindlovu, and Ulundi, the relentless volleys of breech-loading rifles, artillery, and machine guns overwhelmed even the most determined assaults. For the British, the war was a hard lesson in preparation and respect for indigenous forces. For the Zulu people, it marked the destruction of their sovereignty, the breaking of the regimental system, and the end of their independence.

Major Battles of the Anglo-Zulu War (1879)

Date | Battle | British Forces | Zulu Forces | British Casualties | Zulu Casualties | Outcome | Location |

22 Jan 1879 | Isandlwana | ~1,800 men: 1st & 2nd Battalions, 24th Regiment of Foot; Royal Artillery (N/5 Battery, 2 guns); Natal Native Contingent; Natal Mounted Police; irregulars | ~20,000 under Ntshingwayo kaMahole Khoza & Mavumengwana kaNdlela Ntuli | ~1,300 killed | ~1,000 killed | Decisive Zulu victory | -28.3606, 30.6547 |

22–23 Jan 1879 | Rorke’s Drift | ~150 men: B Coy, 2/24th Regiment of Foot; Army Hospital Corps; Royal Engineers (Lt. Chard); Commissariat & Transport staff; stragglers | ~3,000–3,500 under Prince Dabulamanzi kaMpande | 17 killed, 15 wounded | ~300–500 killed | Decisive British defense | -28.3694, 30.5306 |

22 Jan 1879 | Nyezane | ~5,000 men: 3/60th Rifles; 99th Regiment; 2nd Battalion Natal Native Contingent; Royal Artillery (2 guns); Naval Brigade (HMS Active) | ~5,000 warriors | 12 killed | ~400 killed | British victory; led to Siege of Eshowe | -29.2167, 31.6333 |

28 Mar 1879 | Hlobane | ~1,800 men: Wood’s irregulars incl. Frontier Light Horse, Border Horse, Transvaal Rangers, Natal Native Contingent | ~20,000 warriors | ~100 killed | ~1,000 killed | Zulu victory | -27.7167, 30.8667 |

29 Mar 1879 | Kambula | ~2,000 men: 90th Light Infantry; 13th Light Infantry; 1/60th Rifles; Royal Artillery (two 7-pdrs); Natal Native Contingent | ~20,000 under Mnyamana Buthelezi | ~80 killed | ~2,000 killed | Decisive British victory | -27.7833, 30.6167 |

2 Apr 1879 | Gingindlovu | ~5,000 men: 3/60th Rifles; 91st Highlanders; Naval Brigade (Gatlings, rockets); 99th Regiment; Natal Native Contingent | ~10,000 warriors | ~13 killed | ~1,000 killed | British victory; relief of Eshowe | -29.0833, 31.4667 |

4 Jul 1879 | Ulundi | ~17,000 men: 1st & 2nd Battalions 24th; 58th; 80th; 90th; 94th; Royal Artillery; 17th Lancers; Mounted Infantry; Natal Native Contingent | ~20,000 under King Cetshwayo | ~100 killed | ~1,500–2,000 killed | Decisive British victory; end of war | -28.3000, 31.4167 |

Bibliography

Dominy, Graham. “Frere’s War’?: A Reconstruction of the Geopolitics of the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879.” Southern African Humanities 5, no. 10 (1993): 189–206.

Knight, Ian. Zulu Rising: The Epic Story of Isandlwana and Rorke’s Drift. London: Pan Books, 2010.

Knight, Ian. The Zulu War, 1879. Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2003.

Laband, John. “’War Can’t Be Made with Kid Gloves’: The Impact of the Anglo-

Zulu War of 1879 on the Fabric of Zulu Society.” South African Historical Journal 43, no. 1 (2000): 179–196.

Laband, John. “Zulu Strategic and Tactical Options in the Face of the British Invasion of January 1879.” Scientia Militaria: South African Journal of Military Studies 28, no. 1 (1998): 1–14.

Lock, Ron, and Peter Quantrill. Zulu Victory: The Epic of Isandlwana and the Cover-Up. London: Greenhill Books, 2002.

Raugh Jr., Harold E., ed. Anglo-Zulu War, 1879: A Selected Bibliography. Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press, 2011.

South African Military History Society. Goldswain, G. C. “The Anglo-Zulu War of 1879 – Isandlwana and Rorke’s Drift.” Military History Journal 4, no. 4 (December 1978). Accessed September 6, 2025. https://samilitaryhistory.org/vol044gc.html.

BritishBattles.com. “Battle of Isandlwana.” British Battles and Medals. Accessed September 6, 2025. https://www.britishbattles.com/zulu-war/battle-of-isandlwana/.

Historic UK. “Timeline of the Anglo-Zulu War.” Historic UK: The History and Heritage Accommodation Guide. Accessed September 6, 2025. https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofBritain/Timeline-of-the-AngloZulu-War/.

Comments