Appomattox Courthouse

- Ray Via II

- Aug 25, 2025

- 5 min read

On July 2 of this year, we visited the Appomattox Courthouse Museum as part of our trip through central Virginia. The day was warm and bright, and before even reaching the visitor center, we passed the solemn Confederate cemetery just off the main road. Rows of small, simple headstones stood in neat lines beneath the summer sun, marking the resting place of soldiers who never saw the end of the war. A short distance away, a lone cannon sat on the grassy slope near the

entrance, its dark iron barrel aimed silently across the field, a quiet but powerful reminder of the violence that once swept through this peaceful countryside.

Approaching the historic village, the horse-and-buggy era rock roads, carefully maintained and winding through the landscape, offered a tangible connection to the 19th century. These rugged, uneven paths allowed us to imagine the slow, deliberate movement of troops and civilians alike during that tumultuous spring of 1865. The sound of hooves on the gravel and the feel of the rough terrain underfoot made it easy to picture the exhausted soldiers and commanders traveling the same roads, pursuing the final campaign that would bring the Civil War to its close.

That campaign began with the collapse of Petersburg and Richmond in early

April, when General Ulysses S. Grant’s army finally broke through Confederate defenses after months of brutal siege. General Robert E. Lee withdrew his battered Army of Northern Virginia westward, hoping to link with Confederate forces in North Carolina. For nearly a week, Lee and his men fought a desperate retreat, clashing with Union forces at Sailor’s Creek, Cumberland Church, and High Bridge. At Sailor’s Creek alone, Lee lost nearly a quarter of his army, killed, wounded, or captured—including several of his best generals. Hungry, exhausted, and hemmed in on all sides, the Confederates pressed west toward hoped-for supplies at Appomattox Station, only to find Union cavalry had seized the trains before their arrival. By April 8, Lee’s options were gone, and on the morning of April 9, after a final attempt to break through Union lines failed, he chose surrender over further bloodshed.

President Abraham Lincoln approached the prospect of surrender with a spirit of reconciliation and healing. He instructed Grant to offer generous terms, designed not to humiliate but to reunite the fractured nation. Lincoln’s guiding vision of “malice toward none, with charity for all” aimed to bind the wounds of war without sowing resentment. Yet this vision was cut short. Only five days after Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, Lincoln was assassinated at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C., just as the country began to reckon with the challenges of Reconstruction. His death cast a pall over the nation and left unanswered questions about how much gentler the postwar era might have been under his guidance.

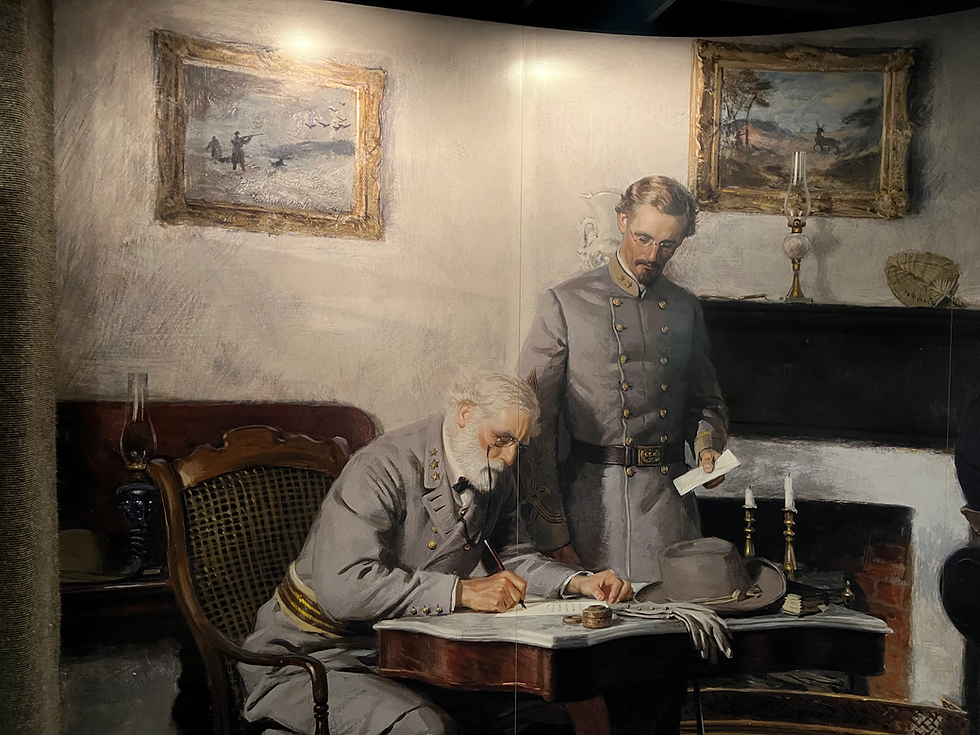

The McLean House, where the surrender was signed, embodies the strange coincidences of the war. Its owner, Wilmer McLean, famously claimed that the war had started in his front yard at the First Battle of Bull Run, where his property was caught in the chaos, and ended in his parlor at Appomattox. Though this tale was embellished for dramatic effect, it captured the imagination of generations, and his home has come to symbolize both the personal cost and the closure of the war. Inside that modest parlor, two weary generals agreed upon terms that would define the beginning of national reconciliation.

Nearby, the presence of outbuildings adds another layer of history often overlooked. A separate kitchen and small slave quarters stand as reminders of the very institution at the heart of the conflict. Their plain and utilitarian construction contrasts sharply with the more comfortable living spaces of the owners, underscoring the unequal conditions endured by the enslaved. Walking past them, we were reminded that emancipation was not just an abstract political decision—it directly changed the lives of those who lived and labored on this soil.

Not far from Appomattox lies Israel Hill, one of Virginia’s earliest free Black communities. Founded in the early 19th century by emancipated people who purchased land, it became a haven for independence and resilience. Its proximity to the courthouse underscores the broader social transformation the war accelerated: from bondage to freedom, from division to the beginnings of a more inclusive society. Israel Hill’s survival into the modern day testifies to the determination of those who built new lives despite overwhelming challenges.

The visitor center, situated in the reconstructed courthouse, boasts a rich collection of artifacts that directly connect to the events of 1865. Among them are personal items from soldiers and residents, as well as symbolic objects tied to the surrender. We explored the exhibits at our own pace, pausing to take in details that made the history feel tangible. A short historical film plays regularly in the on-site theater, offering vivid context before or after touring the grounds. We made time for the film, which provided a clear and emotional introduction to the events of April 9, 1865, and set the tone for the rest of our visit.

Although we skipped the guided tour, the presence of rangers and knowledgeable volunteers made it easy to see how engaging the formal programs could be. Their talks and tours, often infused with dramatic storytelling, help transform the experience from a simple walk-through historic building into a vivid journey into the past. The combination of well-researched interpretation and the preserved setting allows visitors to imagine the surrender as if it were unfolding before them.

The park’s layout retains the feel of a small village, with walking trails, interpretive signs, and scenic open areas. It is a tranquil and reflective place, where the atmosphere makes it easy to envision both the relief and the uncertainty that followed the war’s end. We appreciated the quiet pace, but the summer sun reminded us that shade is limited, so water and sun protection are wise to bring. Without the structure of a tour, we wandered freely, spending more time at places that drew our interest, such as the doorway of the McLean House, where the final act of the war’s drama had been signed into history.

Most guests find that two hours is sufficient to watch the film, explore the exhibits, and walk the grounds at a comfortable pace; however, those with a deep interest in Civil War history may easily spend longer. For us, the visit struck a balance between education and reflection. The site’s strengths lie in its historically significant location, its well-preserved and reconstructed buildings, and the depth of knowledge shared by rangers and volunteers. The setting is quiet and evocative, ideal for contemplation. The only considerations are the limited shade during warmer months and the fact that younger visitors with less interest in history may connect best through the film or ranger-led talks.

Overall, the Appomattox Courthouse Museum provides a powerful and well-curated glimpse into the conclusion of the Civil War. It combines authentic preservation, thoughtful interpretation, and a peaceful landscape to create an experience that is both educational and emotionally resonant. It is a place where the echoes of history remain, and where even a self-guided visit leaves a lasting impression.

Comments